The Language and Etiquette of the Fan – A True Sign Language or Just a Myth?

Today, we often hear that fans were used in the Victorian era to convey secret messages to friends or admirers. Although men also used smaller fans in the early 19th century, it was ultimately women who adopted them, supposedly mastering a kind of fan language—similar to the signals sometimes made with gloves or parasols. For example, twirling a fan in the left hand was said to secretly mean “We are being watched,” while gently gliding the fan along one’s cheek could indicate: “I love you.”

A Language with More Than Twenty Gestures

As a lady in those days, simply fluttering a beautiful fan already drew attention. But whether the fan language was actually understood—and practical to use—is uncertain. There were more than twenty different gestures (soon you’ll be able to read more about the gestures) , which had to be performed discreetly. It’s doubtful whether the intended (usually male) recipient understood these secret signs at all. So, whether the message truly came across remains questionable.

Fan Etiquette as a Marketing Tool

The so-called fan language gained some recognition after a French fan maker published a list of gestures in the early 19th century—essentially a kind of etiquette guide. The true purpose? To promote fan sales. While the intention behind the publication may have been less romantic than the idea of the language itself, it was still a charming notion. The leaflet became a great success, and the French fan maker even had the honor of counting Queen Victoria among his clientele.

The Silk Fan in Art

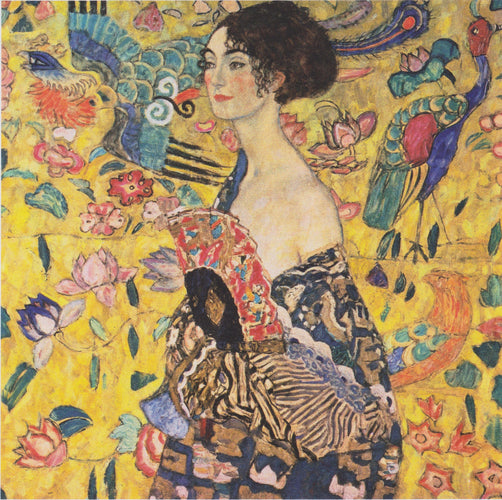

Though the etiquette surrounding the fan was likely more myth than reality, it certainly captured the imagination. It is prominently referenced in Oscar Wilde’s play Lady Windermere’s Fan, for instance. And in the visual arts, the close connection between women and their, often precious silk, fans has been immortalized. Consider the many portraits by Spanish painter Ignacio Zuloaga, as well as earlier famous works by Gustave Klimt, Isabella by Simon Maris, or the paintings of Velázquez.

All the more reason to step out with a beautiful fan of your own!

Ignacio Zuloaga, My Uncle Daniel and his Family, oil on canvas, 205,1 x 289,5 cm, 1910, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Gustave Klimt, Dame met Fächer, 100 x100 cm, Oil on canvas, via Wikimedia Commons